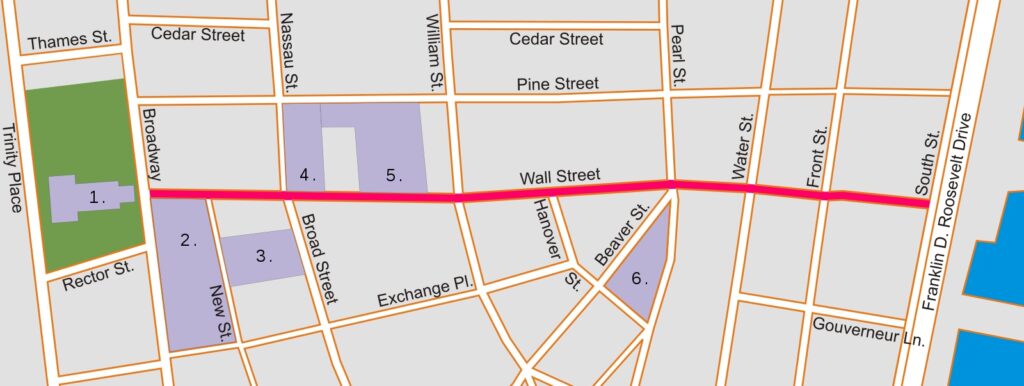

Wall Street, today a canyon of tall buildings in New York’s historic Financial District, is not only one of the most famous streets in the United States, it’s also a stand-in for the entire American financial system.

One of the first facts you learn as a student of New York City history is that Wall Street is named for an actual wall that once stretched along this very spot during the days of the Dutch when New York was known as New Amsterdam.

The particulars of the story, however, are far more intriguing. Because the Dutch called the street alongside the wall something very different.

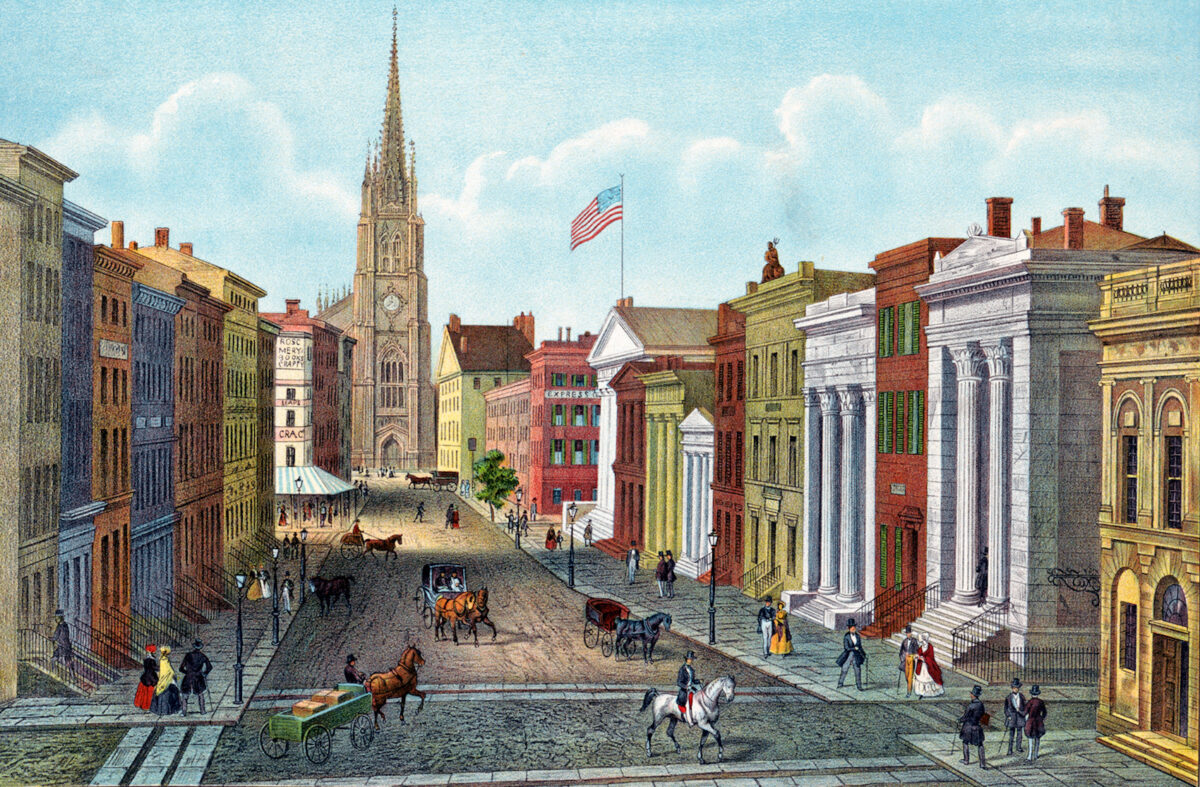

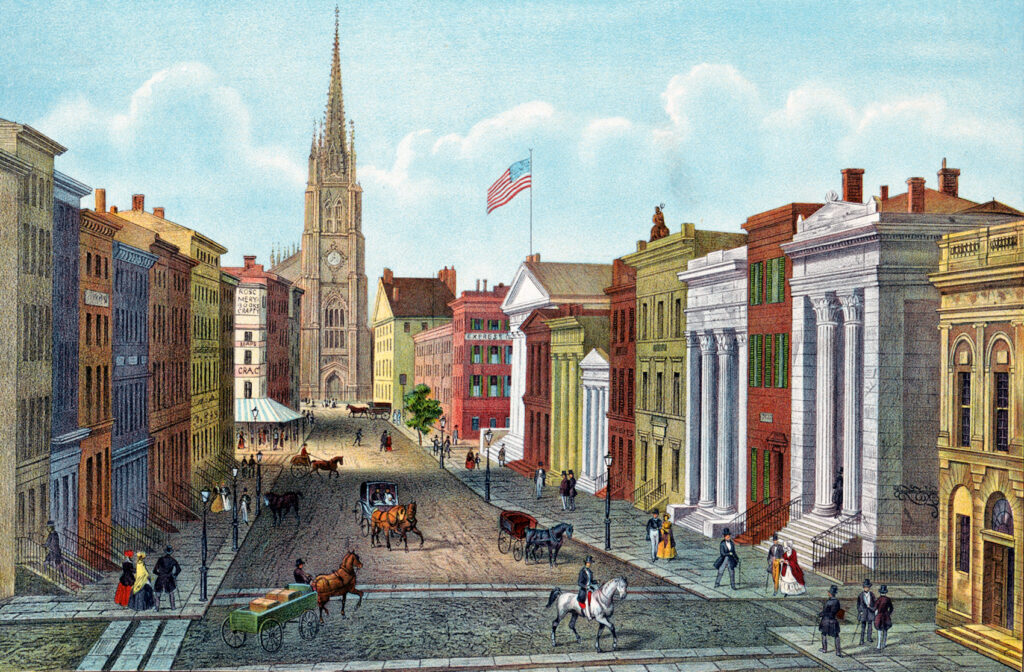

During the colonial era, the wall was torn down and turned into the center of New York life, complete with Trinity Church, City Hall and a shoreline market with a disturbing connection to one New York’s financial livelihoods — slavery.

So how did this street become so associated with American finance? The story involves Alexander Hamilton, a busy coffee house and a very important tree.

LISTEN NOW: HOW WALL STREET GOT ITS NAME

FURTHER LISTENING:

After listening to the show about Wall Street, check back into these prior episodes for further adventures relating to this story.

Other great things to read: Start with this excellent five-part deep dive by Michael Lorenzini from the NYC Department of Records & Information Services about New Amsterdam streets and the origin of the name. The brilliant James Nevius wrote about the history of Wall Street for Curbed. Mapping the African American Past holds excellent resources about the 1711 slave market. And a visit to the New Netherland Institute is always a worthy use of your time.

On this website you can read articles about Federal Hall, Charlie Chaplin on Wall Street, the Wall Street bombing of 1920 and this rather interesting article about Peter Stuyvesant and drinking alcohol.

This podcast is inspired by the article below, which ran in 2017 (and was itself based on an earlier article on this website).

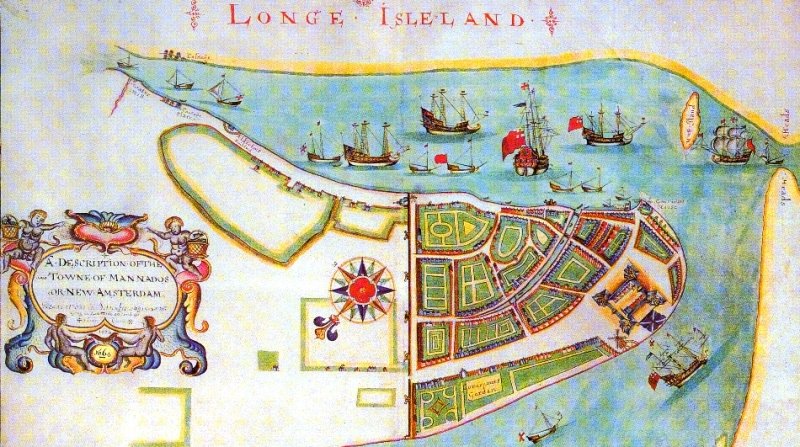

A simplistic but colorful view of “Man Mados” or “New Amsterdam” in 1664 (click in to inspect the detail)

There was most definitely a walled fortification nearby on New Amsterdam’s northern boundary, and it certainly did stretch along about the same area as Wall Street does today.

But the present name seems to be a formation of mixed meanings that only a tangle of languages and hundreds of years of history can create. The Dutch themselves referred to an actual street alongside the waterfront that ran up to and alongside the wall as the ‘Cingel’ — according to old history, meaning “exterior, or encircling, street.”

But ‘De Waal Straat’, as it was also known, was also the center of a small Walloon community in New Amsterdam, and some believe the name comes from them. The Walloons were French-speaking Belgians who were among the first European settlers, arriving in the New World as part of a contingent hired by the Dutch West India Company.

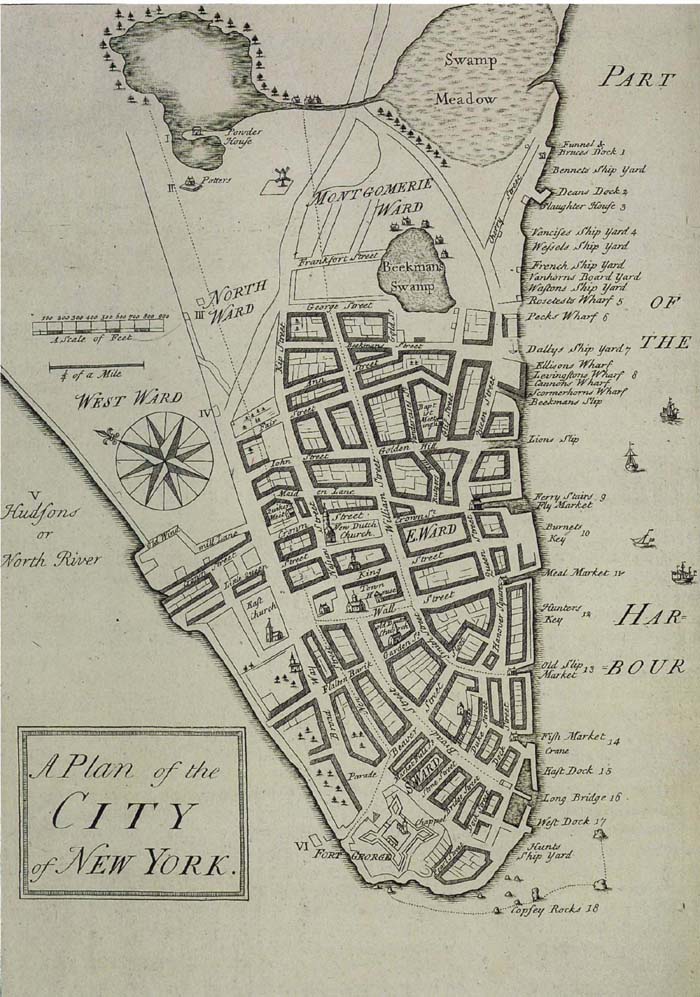

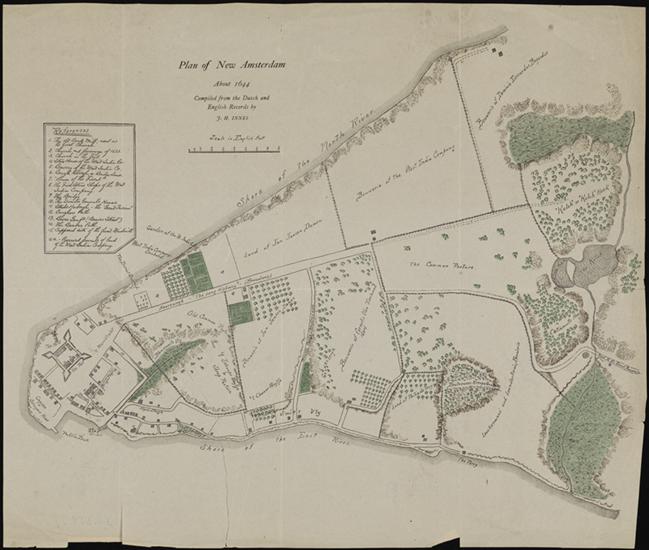

A map of New Amsterdam, indicating the layout from about 1644, well before a wall was constructed.

The real reasons for New Amsterdam building its famous wall are also up for grabs. It’s commonly held that an original wooden palisade was erected in 1644 in defense of Indian attacks, and certainly, the residents of New Amsterdam did their part to rile the anger of the native landowners.

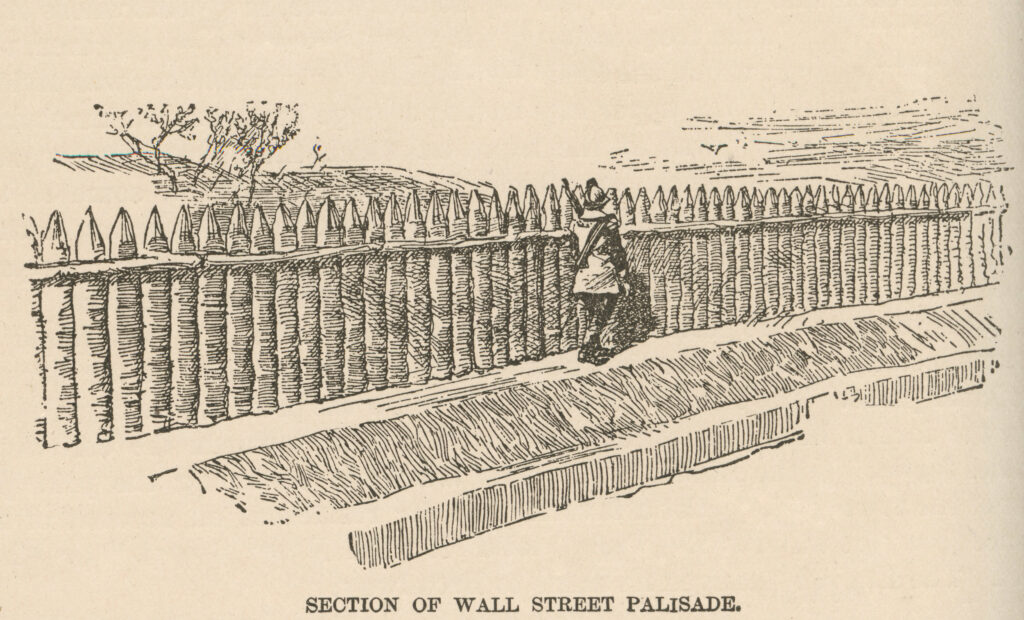

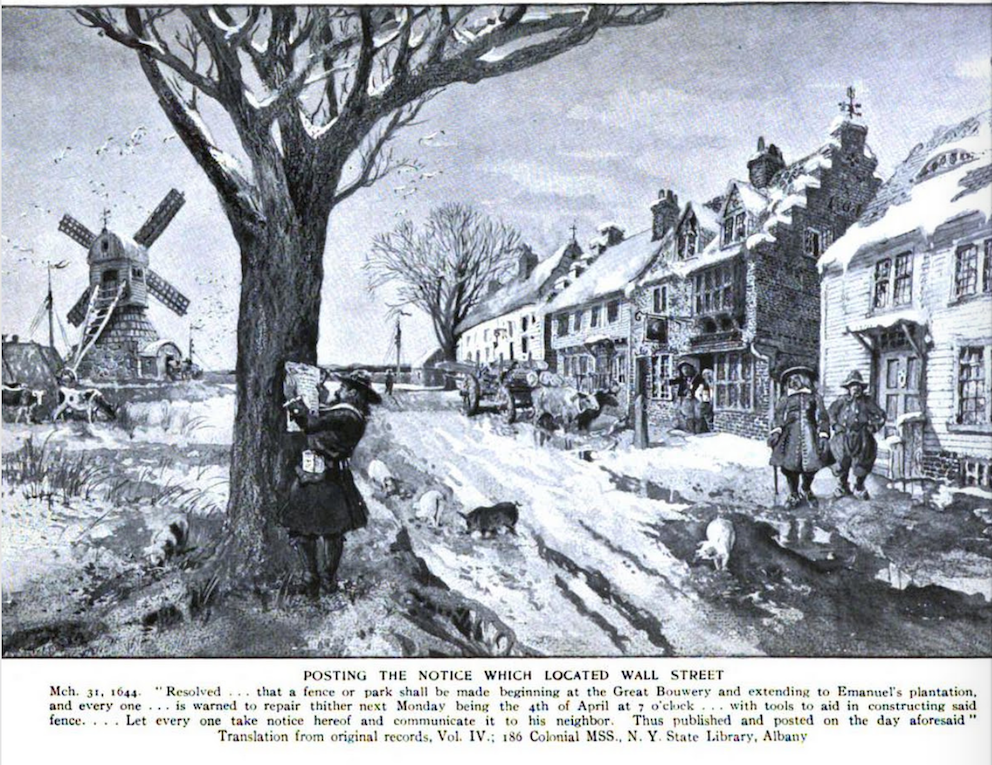

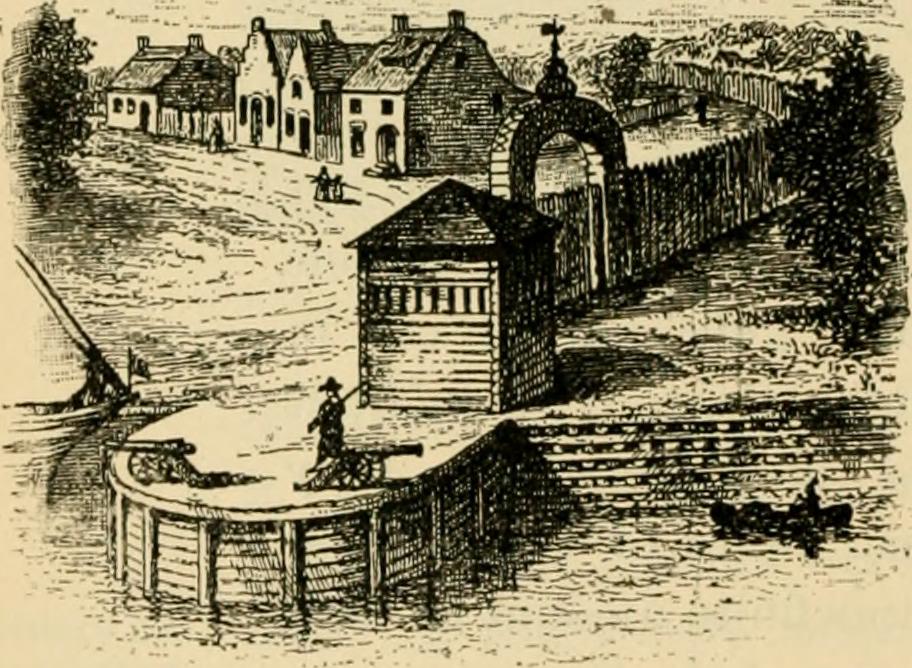

Below: A fanciful illustration from Harper’s Magazine, 1908, imagining New Amsterdam and the construction of the original ‘wall’.

But the Dutch had been living at the tip of Manhattan for over 25 years by the time the sturdier wall was built in 1653. In truth, it was commissioned to keep out a different sort of enemy.

You’ll be pleased to know that director-general Peter Stuyvesant was the man who ordered the construction of the wall — in his words, “to surround the greater part of the city with a high stockade and small breastwork” — to replace the inadequate wooden barrier that had previously marked the city’s northern border.

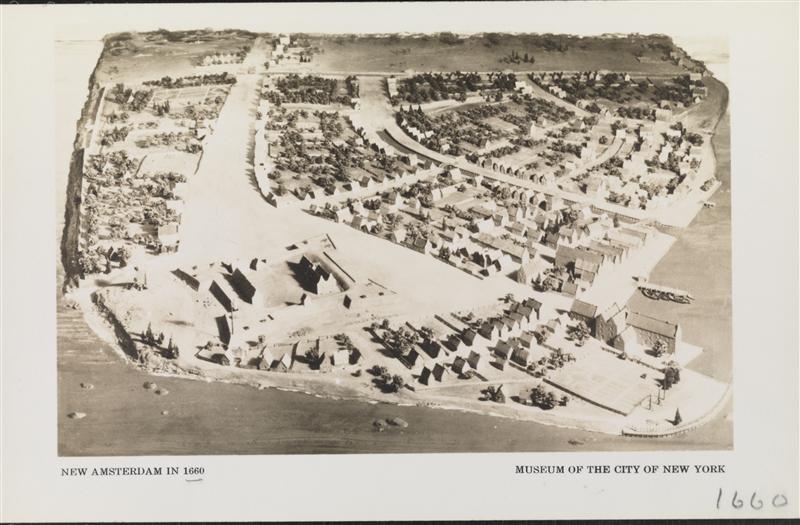

A model of New Amsterdam made in 1933, clearly showing how sudden the city borders stopped thanks to the wall.

This was an incredibly important year for New Amsterdam in two respects. In February 1653, New Amsterdam was chartered as an official Dutch city.

Although Stuyvesant was quite against the outpost receiving such official recognition, he eventually took advantage of it, appointing the first town council himself rather than putting it up to such trivial inconveniences as elections.

But in 1653, the tides of the motherland spilled onto their shores as the war between England and the Netherlands threatened the remote and undefended new city.

The Dutch intended to launch ships from New Amsterdam harbor in a battle against the English.

As a result, the English colonies up north were sure to retaliate, either by sea or, feared Stuyvesant, over land, possibly teaming with hostile Indian forces, down through undefended Manhattan island.

Essentially, the wall that helped give us Wall Street was built because Stuyvesant feared attacks not just from Indian tribes, but from the European colonies of Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Haven!

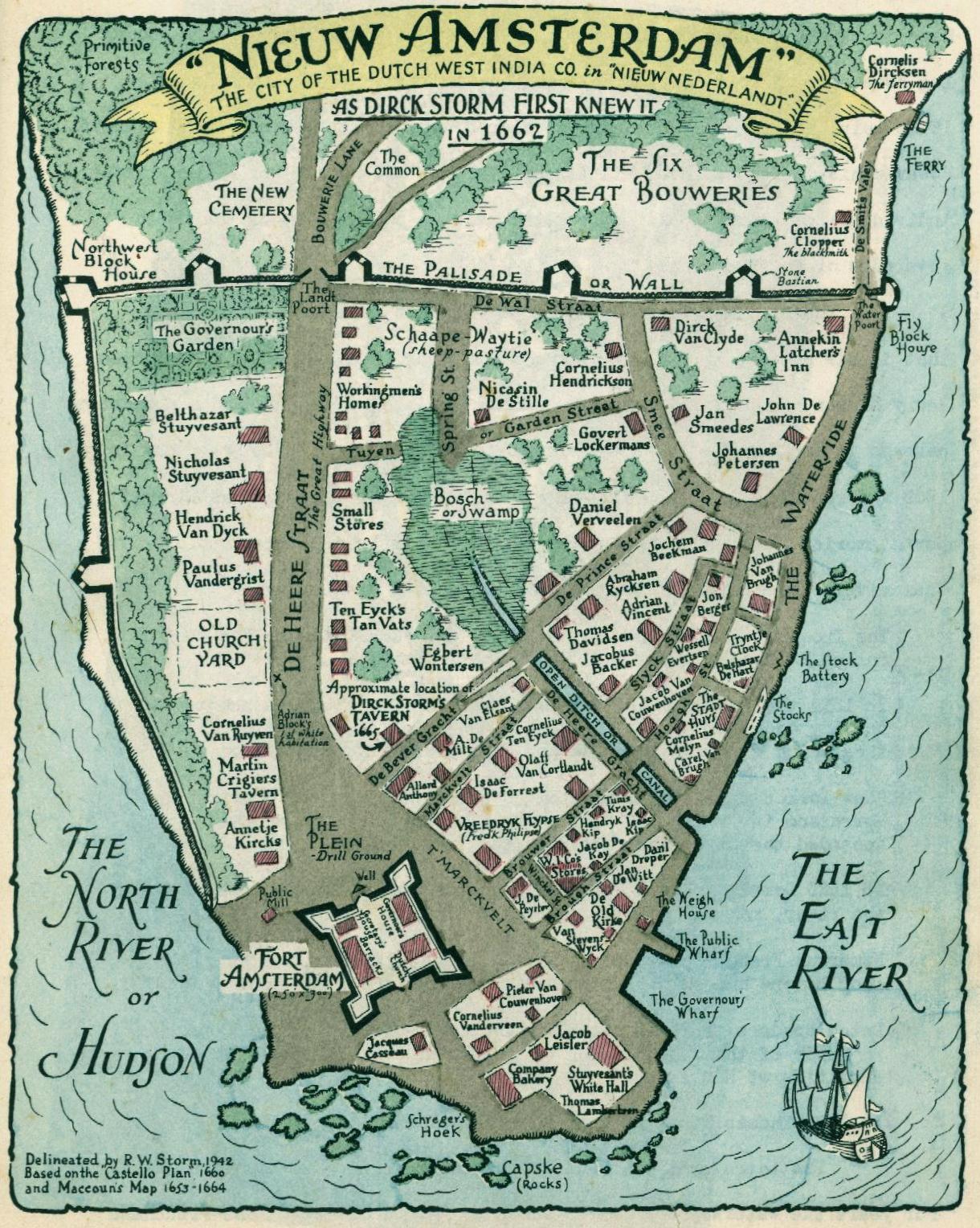

Looking at this more well-known map of New Amsterdam – the Costello Plan of 1660 — one can see the two gates very clearly.

Stuyvesant called upon the 43 richest residents of New Amsterdam to provide funding to fix up the ailing Fort Amsterdam and to construct a stockade across the island to prevent attacks from the north, while it took New Amsterdam’s most oppressed inhabitants — slave labor from the Dutch West India Company — to actually build the wall.

The barrier was constructed out of earth, rock, and 15 feet timber planks sold to the Dutch, ironically enough, by the “notorious“ Englishman Thomas Baxter. In a turnabout that one would expect from hiring your enemy, Baxter later led a group of “Rhode Island marauders“ and pirated Dutch fishing ships.

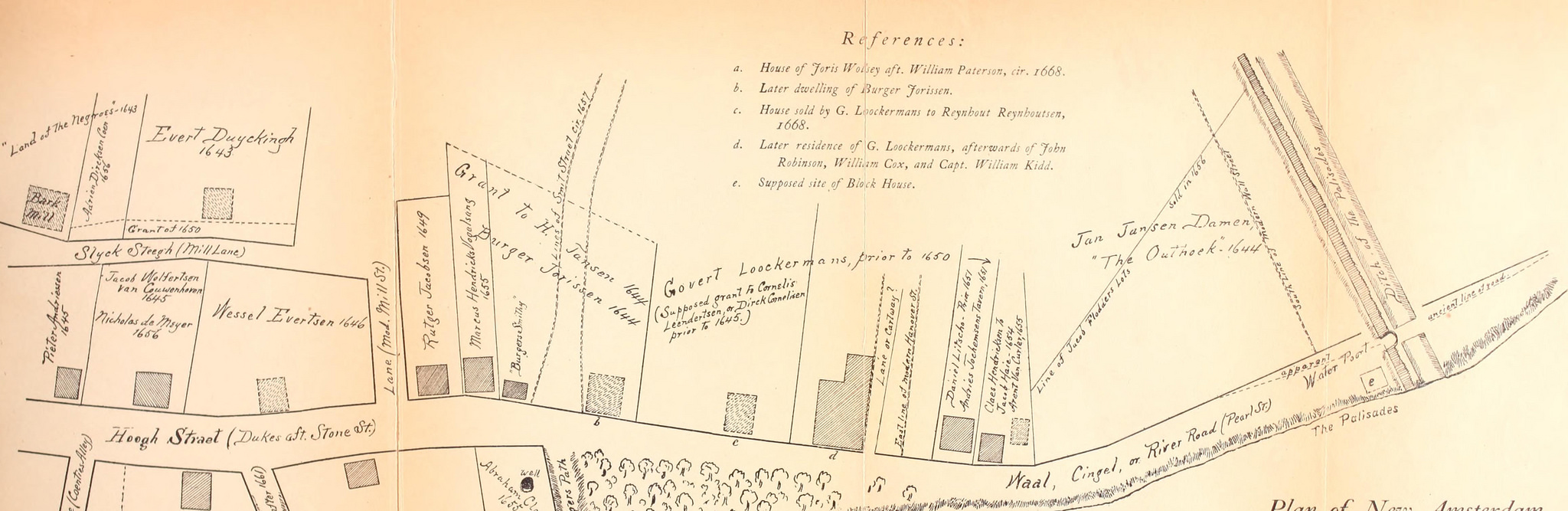

Early in the 1660s, the Dutch upgraded its wall to include brass cannons and two sturdy gates — one at today’s intersection of Wall and Broadway (for land), the other at Wall and Pearl Street (according to an early account, a water gate and access to a ‘river road’).

Below: A detail from a map of New Amsterdam’s eastern side, clearly showing the water gate, and an illustration from 1908 of that eastern gate:

The British took over New Amsterdam in 1664 and renamed it New York, but the wall still remained, becoming more a relic than a serious defense.

By the turn of the century, the fear of land attacks had almost completely subsided and the city was beginning to feel crowded. So in 1699, the wall was torn down with some of the material salvaged to help construct a new City Hall at the corner of Nassau Street and the newly christened Wall Street.

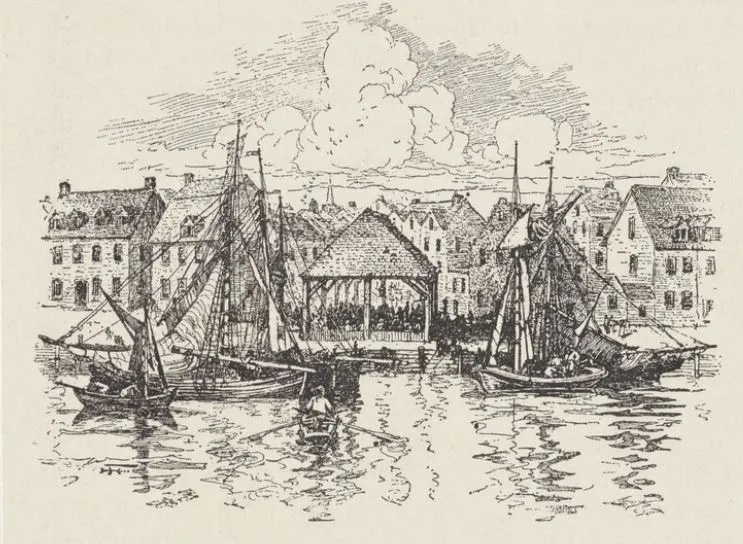

In 1711 a slave market was built on Wall Street along the eastern shore, remaining there until 1762.

When the British were forced out in 1783 by the Americans, the City Hall building was finally renamed Federal Hall — the first official center of American government.

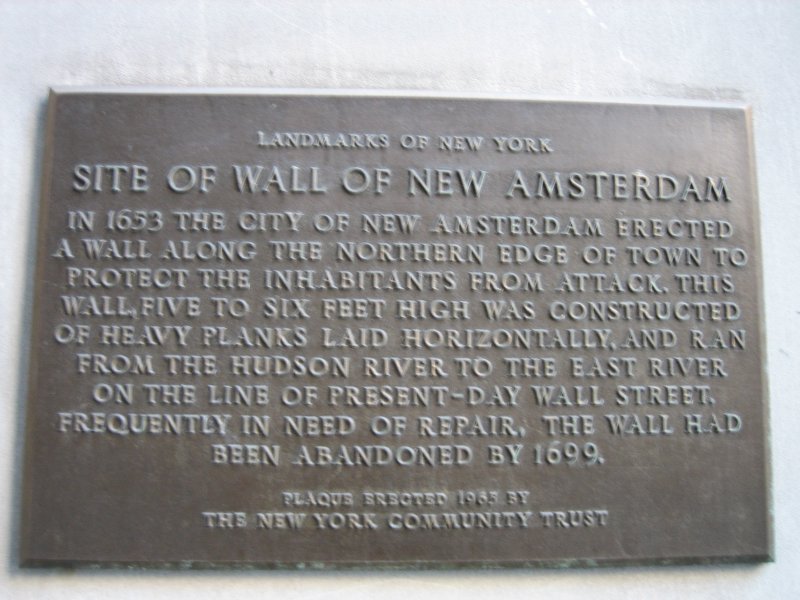

A plaque honoring the old wall sits today at the corner of Wall and Broadway, where the gate to the city once opened: